I’ve argued that Rights income needs to be understood and recognised more widely as far more than the icing on the cake for publishers. I also want to make the case that the Rights function can also be at the cutting edge, the driver behind exciting new developments in the publishing industry.

These days, the biggest of our global publishing conglomerates have a very wide reach, not just into hundreds of countries but into different languages through sister companies around the world. They publish in multiple formats, both physical and digital, and through different forms of content delivery, from on-line material to downloads and streaming. But this was not always the case, and even today, smaller publishers or new start-ups may not have the resources or expertise to spread their content this widely.

Reaching the parts that others cannot reach

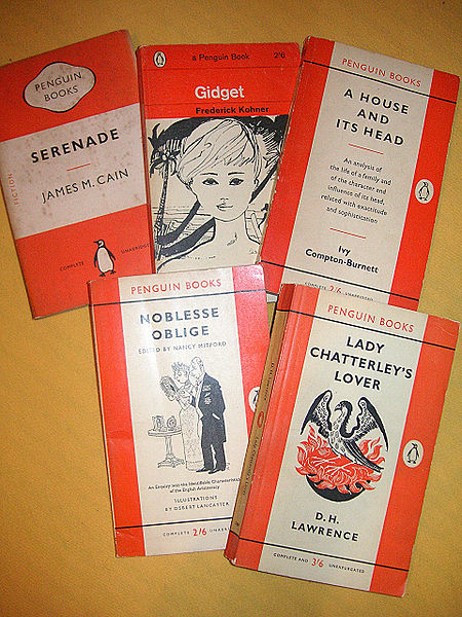

This is where the sale of Rights comes into its own. Rights reaches the parts that others cannot reach, and opens doors for publishers and authors. This has been demonstrated throughout publishing history and is as true today. Take paperback rights as a historical example: in my early days in publishing, our biggest money-spinner, as a publisher of hardback books, was licensing U.K. paperback reprint rights. Over time, those mass-market paperback sales to a wider public at a lower price, became essential to the financial success of a title. This led to company mergers, the scooping up of existing paperback houses by larger companies, or the development of in-house paperback imprints. What had been a strong licensing strand became instead an integral part of a company’s own business.

This is where the sale of Rights comes into its own. Rights reaches the parts that others cannot reach, and opens doors for publishers and authors. This has been demonstrated throughout publishing history and is as true today. Take paperback rights as a historical example: in my early days in publishing, our biggest money-spinner, as a publisher of hardback books, was licensing U.K. paperback reprint rights. Over time, those mass-market paperback sales to a wider public at a lower price, became essential to the financial success of a title. This led to company mergers, the scooping up of existing paperback houses by larger companies, or the development of in-house paperback imprints. What had been a strong licensing strand became instead an integral part of a company’s own business.

More recently eBooks, and audio have followed a very similar route. In the early days of eBooks, it was common for agents and even some publishers to license eBook rights to a company who was proficient with the technology and had the ability to reach the consumer. It soon became clear that publishers needed to bring this in-house: not only was the eBook a viable new medium for reading, but eBooks directly competed with the printed works, so the two publishing strands needed to be completely integrated. It is now rare for a publisher not to publish in both digital and print editions.

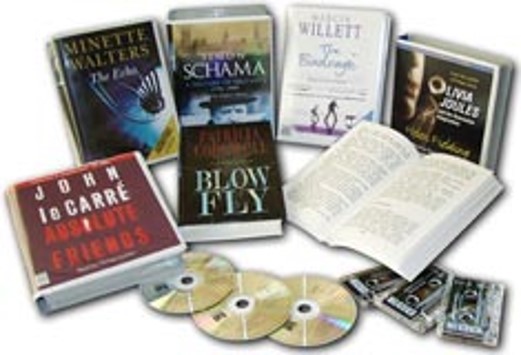

Audio rights, in the days of cassettes and CDs, were regularly licensed out to third parties, who, once again, had the dedicated expertise, contacts and distribution to reach their audience. With the advent of digital audio and key players such as Audible and Storytel, it has rapidly become clear that this is a growing and vibrant market. Publishers have moved quickly both to acquire and retain these rights, employed staff who understand the genre, invested in narrators, producers and studios, to enable audio publishing to be the third crucial strand alongside print and eBooks.

Audio rights, in the days of cassettes and CDs, were regularly licensed out to third parties, who, once again, had the dedicated expertise, contacts and distribution to reach their audience. With the advent of digital audio and key players such as Audible and Storytel, it has rapidly become clear that this is a growing and vibrant market. Publishers have moved quickly both to acquire and retain these rights, employed staff who understand the genre, invested in narrators, producers and studios, to enable audio publishing to be the third crucial strand alongside print and eBooks.

Invest or license?

What’s next, you ask? The film and television production business has already attracted attention. The arrival of Netflix, Prime, Apple and others has disrupted the traditional Hollywood business model and emboldened publishers and agents such as Penguin Random House and Curtis Brown to create film production arms (Random House Studio and Cuba Pictures). However, this sort of speculative investment is not available to many: most publishers and authors will still have to rely on the film or TV rights being licensed.

Not only could a publisher find itself investing in areas which are not part of its core business, but, more dangerously, investing in areas which are still developing, areas which have not yet proved themselves to be either viable or profitable. I am thinking of publishers who, back in the 1990s, invested in interactive CD-ROMS believing this was the future of illustrated reference works, or, more recently, those who put their faith in all-singing, all-dancing interactive eBooks and apps. Just because you can do something, doesn’t necessarily mean you should!

This is where Rights comes in. Licensing gives you the opportunity to experiment at one remove, and, should things start to take off, to move swiftly into development yourselves.

Rights as a stepping stone

If you use licensing as a stepping stone to business development, you are able to experiment using someone else’s money, with no investment and little financial risk, and learn about a new business model at one remove. Provided that you protect yourself by limiting that licence carefully (in the way that every Rights Manager is familiar with: by length of licence period, by territory and language, by specific format or channel), if it works, you can stop licensing and start doing it yourself.

This approach is particularly attractive in our fast-developing world where new opportunities are arising all the time. It takes time to get to grips with new technology (such as the use of AI), or new and unfamiliar financial arrangements (such as subscription models). We might be concerned whether any substantial income will make its way back to the original publisher or the author (block-chain, anyone?). This can lead to our being over-cautious and holding back. Perhaps it’s time to let Rights forge a path and be your experimental publishing arm.

When and if you decide it’s time to bring it all in-house, and Rights lose that precious income stream, where does that leave the Rights team? Well, we may sulk briefly, but we’ve been here before. We know there are plenty of new and exciting opportunities out there where Rights can lead the way!

Diane Spivey

January 2023